Some remarks on the readymade and painting – as well as some notes on Leonardo da Vinci and Thomas Kluge:

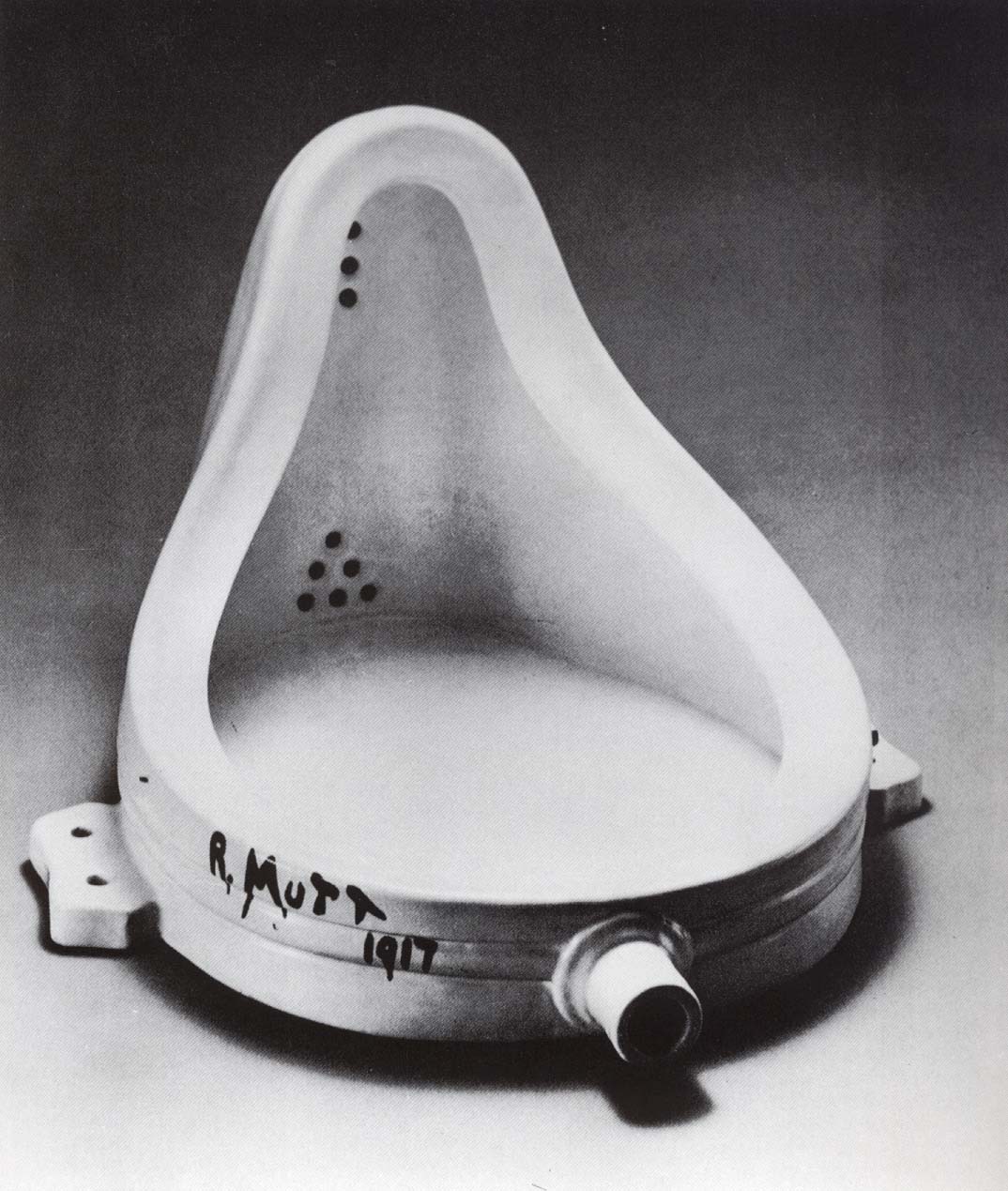

The readymades have made Marcel Duchamp both famous and notorious. The urinal ”Fountain” from 1917 can still make some people very angry. But Duchamp is more than the provocative inventer of the readymade: First he painted pictures in different modern styles, then he launched the readymades and denounced painting – the last mentioned happened roughly at the time of the Dada movement (1916 – 1922). He also created several works on doors and windows and installed a mile of string in a gallery for a surrealist exhibition (1942). This was long before installation art became the ”state of the art” in contemporary society. He had a keen interest in optics, he studied old perspective treatises, made stereoscopic drawings and also mastered the difficult techniques of anamorphosis (distorted pictures of perspective). And the viewer was very important for him – she was his co-creater. In his last major work Étant Donnés (1946 – 1966) this is expressed quite literally: You have to put your eyes to the peepholes in the old wooden door before you – so to speak – will create the picture of the inside of the work on your retina.

But what I first want to express here relates mostly to the readymade, which I understand as a project related to painting. The readymade were necessary at the time or at least they became necessary later on in the 20th century – more accurate – after abstract expressionism. One might say that this kind of painting, which culminated around 1955 – marked the end of the media as a metaphor for art. Of course painting still exists after the end of abstract expressionism and it can still be great, but it is no longer ”the best media” – i.e. with the intention to depict an almost endless space with an innate substance. Clearly painting still has this ability to render space, but most often the modern and contemporary painters prefer to underline the flatness of the painted canvas and thereby they avoid the illusionistic space. After abstract expressionism – in the sixties – the readymade became of enormous importance for conceptual artists, installation artists and others. For example in Joseph Kosuths work ”One and Three Chairs” from 1965 – a work which has the form of an installation – the artist make use of a readymade: namely the real ordinary chair. The chair functions as a figure or motive in the work, and the readymade chair is not by itself a piece of art. It is the artists brainwork – done in advance of the work – which constitute the installation (including the chair) as a work of art.

Had Duchamp not invented the readymade – somebody else should have done so. But at that time (1917) painting had more to offer – that is additional new styles. That is probably why the readymade is not really in use by artists before the sixties. (The surrealistic objects from the 1930s are often composed by several readymades, but that is another story – although there is familiarity between Duchamps readymades and the surrealistic objects).

Well – to a start they appeared in the beginning of the 20th century. They appeared at a very speciel time in the history of painting. Around the time for the first readymade (1913) Kandinsky and others had bravely invented abstract painting, which greatly renewed and prolonged the existence of the media as a favorite work of art. Gradually Kandinsky had abstracted himself from reality and the world of things and in texts he also – and logicly enough – argued for spirituality in art. The spirit has no body or figure as such – it is not a thing in the world, which can be described. According to Kandinsky abstract art could serve as a source for spirituality in a society influenced by materialism and industrialism.

Now the invention of abstract painting is a rather radical thing compared to the fact that painting had been figurative – at least in the western world – since the old Egyptians. In Egyptian wall paintings space is not articulated and figures are not what we usually call naturalistically expressed, but this is not a serious problem for the viewer: the pictures are still figurative and you can understand a lot.

Egyptian art inspired Greek and Roman art, which developed a more naturalistic mode that later gave birth to renaissance art and so forth. Even in the middle ages painting was figurative although anti-naturalistic and more abstract and decorative.

This figurative tradition and the naturalistic way of rendering figures as well as perspective began to disappear from paintings in the last half part of the 19th century. The great tradition had frozen stiff and something new was required. Modernist painting is far from always completely non-figurative, but usually the style of the painting is the most important part of the work – this is what bind most of the many different styles together. The radical new way of painting was – more or less – shocking for the ordinary public until approximately 1955, but this shock is know forgotten and almost everybody is today used to the abstract way of painting. During the cold war abstract painting also became a sign of democracy, education, culture, freedom, tolerance and last but not least: the western part of the world.

Many abstract painters have theorized on their art and much interesting thought-provoking new stuff has been raised on content – often in relation to the emptiness of their flat canvases. Something was won – painting could live on. But something was also missing in abstract painting. What was missing was the condemned material world – the motive in space.

What is also missing in abstract painting is the subjects ability to connect to the world of things and people as well as to concepts.

I will now return to the readymade. It seems to be hard to grasp. Even some art historians turn their back to them. This type will usually concentrate on older art instead.

A readymade is a thing in the world. The majority of them are easy to recognize and thereby related to language. They turned up at a critical time for art – at a time when art and especially painting were in the middle of a crisis for representation. The latter had been the primary goal for painting earlier on.

The genius of the readymade is that it can represent a thing in the world (or a motive) without the use of illusionism. Many of the modern painters criticized the old figurative painters for their use of illusionism which was compared to deceiving the senses. (The old painters was also criticized for their pathetic diligence of craftsmanship which – according to the new painters – led to a boring and deadly expression).

The readymade simply solves the crisis of representation in modernism and shows a way out of the dead end for painting. A readymade LOOKS like its object and IS the object at the same time. It solves the coming and going problem for painting since the philosopher Plato.

Many have criticized the readymades for being too close to reality. And it is true that they are – in certain ways – close to reality. I. e. the material aspect of the readymade is a realistic project. But it materializes a concept, and this demands a willingness to do some abstract thought. And with respect – art has repeatedly struggled with reality. Since antiquity art has tried to cross the border between its own domaine and life. It is for example the project for the so-called trompe l’oeil painting.

When you observe a readymade in a museum (as art or as a material for art) – the phenomenon has just been put in a bigger frame. It is put in an expanded frame compared to a paintings frame. The spectator has walked through that frame.

Sometimes Marcel Duchamp is compared to Leonardo da Vinci. Duchamp is called the Leonardo of the 20th century. This is a great thorn in the side of his detractors. They consider it to be an insult to art in general. An insult to all wonderful and tasteful art.

But in fact – the two of them have many things in common. They are both engaged in the study of optics and they both (primary) relate the human eye to the mind and the intellect. The human eye has many functions. Luckily enough you can ”taste” with your eyes and enjoy a beautiful landscape, a beautiful face, a beautiful painting and so forth. But Duchamp separated the so-called ”retinal” (or tasteful / painterly) function of the eye from the other main function of the eye, which is related to perspective, understanding and intellect. In much modernist painting the artist give priority to aesthetics over elements that can engage the viewer\’s intellect. Alternatively Duchamp wanted – as he said – ”Once again to put painting in the service of the mind.” Art should primarily be an intellectual project.

Leonardo da Vinci was one of the old master painters. He was also an inventor, a scientist and an art theorist. He wrote a book ”On painting” and in the first part of the book (originally called parte prima) Leonardo compares the different artistic medias with each other. This chapter is now related to the concept of paragone – and every written text about the characteristic differences between the various art forms. Leonardos parte prima is filled with astonishing insight – he expresses significant thoughts on this things. He compares painting with sculpture, with music and also (daringly) with litterature. For Leonardo there is no doubt about it – painting is a science – and he places it above the other art forms. He relates painting to optics and the eye: painting represents objects on a flat surface, it is an intellectual and analytic affair rather than a craft (although also a wonderful craft).

In Denmark we have a painter called Thomas Kluge (born 1969). He applied for a position as a student at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Art in Copenhagen 3 times around 1990 – but was not admitted to the school. So he is self-taught. At a certain point of his career he started wearing a beret – in the style of Rembrandt. Often he also stages his hairstyle and clothes likewise.

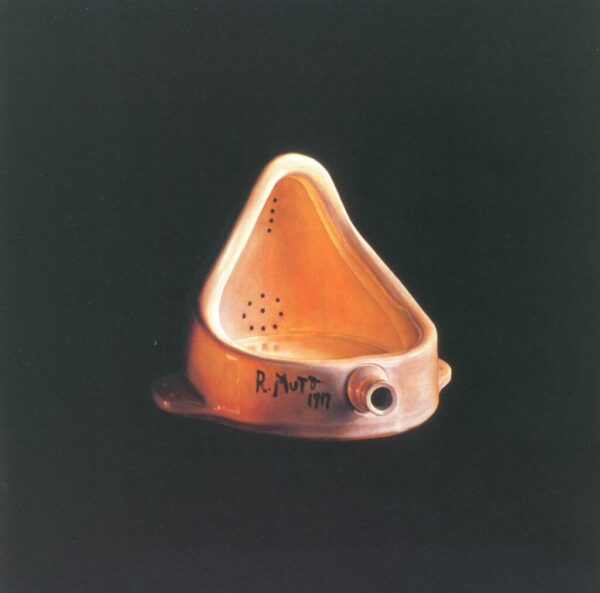

Many in the danish art world don’t like him. He is not a contemporary artist, they say. Now Thomas Kluge has found clients on another parnas or ”mountain”. He does not only paint portraits, but his many pictures of important people and royalties has given him an income. That he paints the rich and the powerful has been held against him (although other artists have done the same). But together with his anti-modern style and the way he looks – this has been to much for his detractors. Thomas Kluges mode of painting is often compared to the style of old masters as Rembrandt and Caravaggio. Their dramatic use of light and shade have influenced Kluge, but his subject matter is contemporary. In 2001 Kluge painted a picture of Marcel Duchamps urinal Fountain. He gave the painting the title ”1917”:

Thomas Kluge has used Duchamps ”Fountain” from Moderna Museum in Stockholm, Sweden as his model for the painting. The urinal is not seen intirely from the front, but Duchamps pseudonym signature and the date is placed almost at the center of the picture (from left to right).

The urinal itself is rendered quite realistically – you note the shiny porcelain material and other elements of the object, which you can easily recognize. But a beautiful golden light seems to elevate the object to a higher sphere. One also notes the format of the painting – a wonderful square. Is it a holy thing?

The artist is well-known for his typical dark – almost black – backgrounds, which also can be seen here. According to Kluge the dark room behind the figure is without borders: It is ment to dissolve the past and the future. And it is true – the object seems very present. It is as if it is in front of the picture. While there is nothing behind it – it is pushed into our own space – the space of the viewer. In my opinion the painting mocks the celebration of its motive – the readymade. At least the picture is raising some questions. The artist is probably expressing his criticism of the contemporary art scene, which celebrates the readymade at the expense of painting. Now Duchamp might not be Thomas Kluges main enemy; but ”Fountain” seems to function for him as a sign for an art world gone into self-oscillation.

As the above written statements reveal: I don’t agree with this skeptical point of view on the readymade and contemporary art. But I think it is alright to have an alternative view on things.

And in fact for me Thomas Kluge seems closer to Duchamp than to the modernist painters, which I guess he would agree on. The toolbox of conceptual art was closer to the old master painters from the renaissance and the baroque periods than to the modernist painters. In interviews Kluge also always emphasizes that his paintings are more about substance and thought than about brilliant technique, fine brushwork, aesthetic sensitivity, beauty and color. Likewise Duchamp gave priority to the intellect. So maybe Thomas Kluge after all is a contemporary conceptual artist?

Below my red bottle-dryer. I bought it in a french type curiosity shop in Copenhagen. Every year at Christmas it is decorated as a Christmas tree.